My work on critical research ethics examines the formal and informal ways that social scientists decide what research is ethical and what research is not. Empirically, the project offers needed evidence to better understand research ethics norms, institutions, and regulations; their diffusion from the United States around the world; and from biomedical research to the social sciences. Theoretically, it situates our current structures of ethical review as historically contingent, and shows how we can better understand them in the context of political economies of knowledge production and the contingent role of higher education.

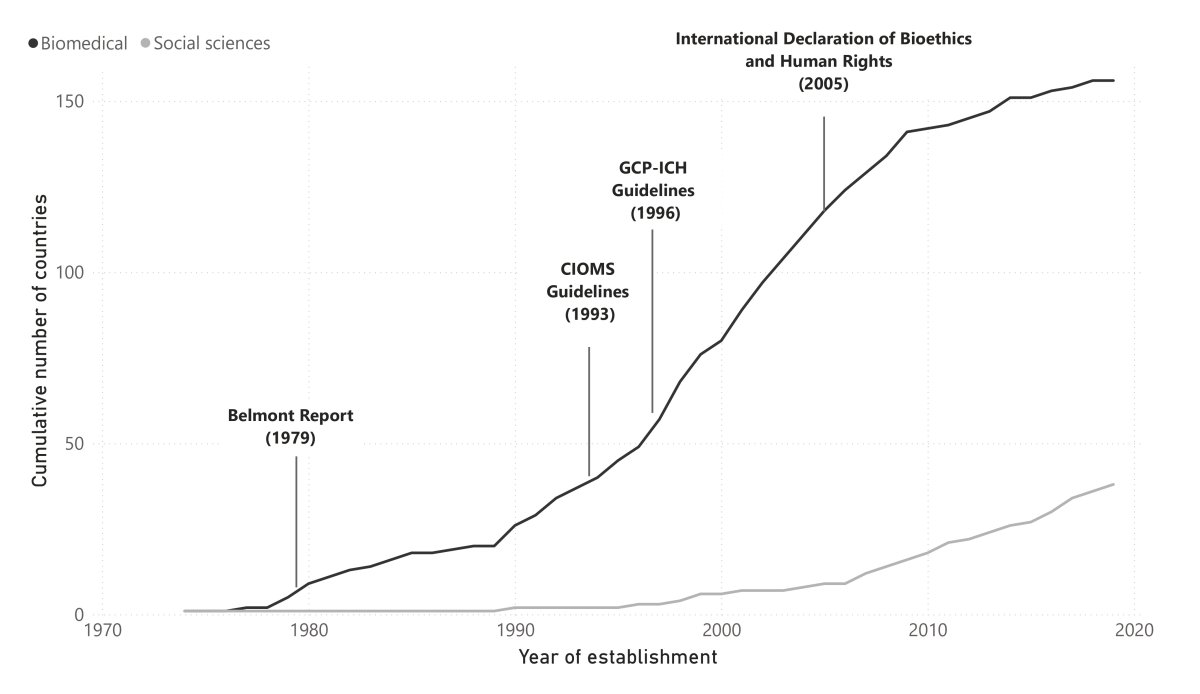

Chart 1: Global Adoption of Requirements for Ethical Review (based on original data, forthcoming in Journal of Peace Research)

In this project, I’ve published a dataset and article on the global status of ethical review in the social sciences. This article, co-authored with Daniel Rincón Machón, shows that while most countries require ethical review for scientific research, it is mainly concerned with biomedical and clinical research (Chart 1). Perhaps more concerningly, when countries or institutions require ethical review in the social sciences, they almost universally use the same principles, guidelines, and institutional processes that were developed for biomedical sciences. My book, and in-progress publications, explore why this is a problem for social scientists, as well as the public and policymakers who rely on social science research to inform public policy decisions.

The project has been funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation's Ambizone grant (2019-2024).

In Progress:

"'Power Dynamics? We Literally Study Them': The Ethics of Student-Involved Research in Political Science" (with Jeremy Moulton, preparing for submission to PS)

Different disciplines in higher education have developed wide-ranging approaches to whether and how they conduct research with and on students in the classroom, or “student-involved research”. This has led to variations in the understanding of and approach to issues of ethics in student-involved research. To date, political science has seen little subject-specific engagement with this matter, even though student-involved research is widely practised. Building on the wider literature on ethics and student-involved research, this article presents findings on how political science students view their own experience of research led by their instructors, and the ethical issues that arise from that participation. We conclude by presenting recommendations for conducting ethically-sound research with student participants.

“Vulnerability in the Guidelines: An assessment of vulnerability in 44 national research ethics guidelines” (preparing for submission to Qualitative Research)

What is vulnerability in qualitative research? For qualitative scholars, vulnerability is a concept best understood through embodied and enacted encounters, which unfold over time and through continually changing and evolving relationships—between the researcher and her respondent, others in the research ecosystem, and the politics of the field itself. Despite the generative reflections taking place in scholarship on vulnerability in qualitative research, the way this concept is operationalised in ethical review processes continues to be guided first and foremost by national and institutional-level policies and procedures. Given their centrality in determining ethical review in practice, this article examines what these guidelines say about vulnerability—what it is and how studies should respond to it. It shows that like the guidelines themselves, definitions of vulnerability are heavily shaped by the assumptions and demands of biomedical research and clinical trials. The article then reflects on how these definitions match up to scholarship by qualitative researchers on the same topic, and reflect on how regulators and researchers might best navigate incongruences.

"The Politics of Beneficence: What Using an Indeterminate Principle Means for Ethical Review in the Social Sciences"

What makes field-based political science research ethical? A widely accepted measure of the ethical quality of research with and on human subjects is beneficence—or the commitment that the benefits of research outweigh its risks. Despite its near-universal acceptance, when it comes to the social and political sciences, this principle is inadequate to assess ethical quality. This is because the concepts of “risk” and “benefit” are so vague that they are indeterminate. To illustrate the extent and stakes of this problem, this article examines four ethical controversies in political science and sociology, studying how scholars articulated and justified harms versus benefits to support incommensurate views of what constitutes ethical research practice. It identifies three mechanisms that sustain the principle of beneficence as indeterminate: ambiguity (the problem of telling what is a risk and what is a benefit), incommensurability (the problem of weighing risks and benefits), and incompleteness (the problem of being sufficiently comprehensive). The findings highlight the need to adapt how ethical principles are implemented by creating processes that foreground the politics of ethical deliberation, the underlying justifications for ethical decision-making, and the assumed public to whom risks and benefits of research accrue.